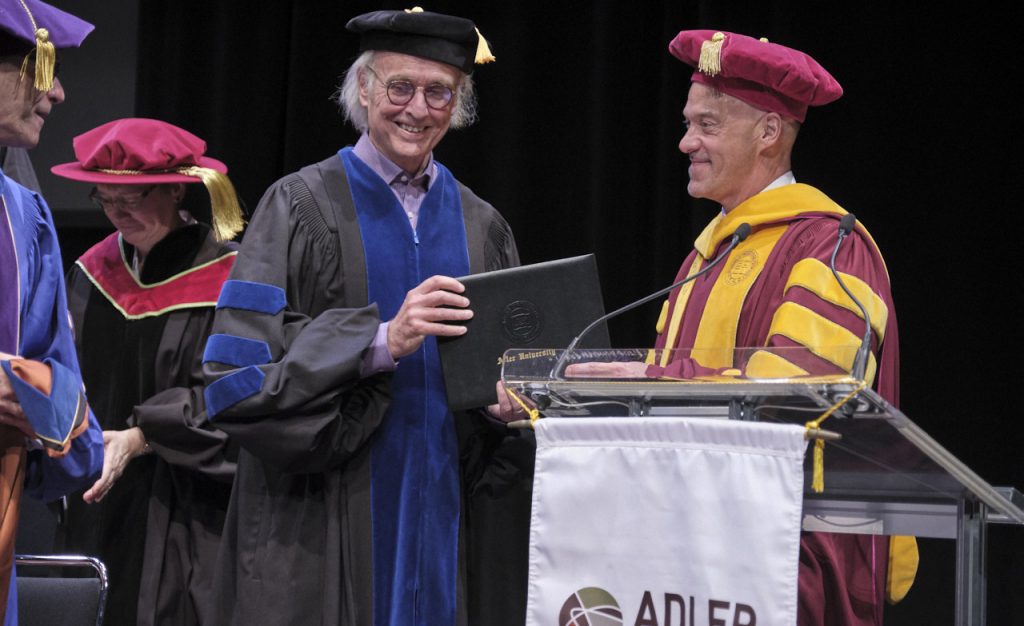

The following commencement address was delivered on October 27, 2019 to the graduating class of Adler University’s Vancouver Class of 2019 by Donald MacPherson, executive director of the Canadian Drug Policy Coalition (Simon Fraser University), as he received an Honorary Doctorate in honor of his work to improve Canada’s approach to illegal drugs.

Thank you so much for this incredible honor. I am delighted to receive this honorary doctorate from Adler University. It means a lot to me and I am quite moved by your decision.

I do have a confession though: I am a lapsed Masters candidate—lapsed, indeed expired, like a parking meter. Out of time. They gave up on me. Yes, I received that letter informing me of my new status as a Masters candidate from the Ontario Institute for Studies in Education many years ago. After two years full-time and two years part-time—ok I’m slow, I guess so slow that I lapsed—my status expired within the academic system. The finality of it all! Don’t get me wrong. It was the best thing I’ve ever done to go down that Masters rabbit hole. The people, the program, the opportunity to spend time going deep into how people learn, how change comes about, and to learn about social movements around the world was one of the best things that I have ever done!

But not finishing what I had started took me to some very dark places. I was so terribly hard on myself and coming down from the mountain without reaching the peak was difficult and devastating for some time. But coming down from the mountain is often the best decision lest the mountain engulf you. So, take care of yourselves and each other as you pursue your next steps. The work I know you are engaged with can be overwhelming, confusing, and challenging.

I had good excuses though for lapsing out on my Masters. I remember my thesis advisor coming across me changing the diaper of our second child on my desk at the university—she is with us today just over there—and he admonished me: “Donald, no more babies till you get that thesis finished.” Shortly after that my wife and I packed up our two kids and headed to Vancouver—me always intending to complete the program from afar. In Vancouver, we had a third child and I began working at the Carnegie Community Centre, at the corner of Main and Hastings, in the middle of what was to become the largest open drug scene in Canada and the confluence of an HIV epidemic among injection drug users and Canada’s worst overdose death epidemic. I was carried away and soon to be on a mission. And remained lapsed!

I feel like I must only accept this honor on behalf of the many in the community and around the world who are working to change what are truly barbaric and simplistic historic approaches to the complex bio-psycho-social-cultural-developmental and often spiritual phenomenon: using psychoactive substances. So many have dedicated their lives to ending the devastating injustices of a global war on drugs, which really is a war on vulnerable, criminalized, and objectified people around the world. After all, those with privilege and power who use illegal drugs rarely meet the players in the criminal justice system.

The recognition by Adler that the work to change the way things are in this country, and indeed the world, in the area of drug policy means a lot to me and indeed tells me much about the depth of commitment to social change of this university. The issue of drug policy reform has NOT been taken up as a critical social justice issue by so many governments, institutions, and other organizations that claim to pride themselves on supporting social innovation and change. Our drug policies are deadly public policies, and so many institutions are complicit in maintaining them.

The commitment to community engagement by this university is a critical part of understanding the catastrophic failure of our current approaches. My education on drug policy issues came directly from the community here in Vancouver; [namely], from working on the corner of Main and Hastings for ten years, talking to people who used drugs and community members about the absurdity of our approach to people who use criminalized substances, which has played out with the same ineffective and harmful results over and over again. That is where I learned so much.

But what advice do I have for you from my many years as a lapsed Masters candidate and drug policy reform advocate?

Don’t look for jobs. Make them up! Look around and see what needs to be done and write the job description you want to have and shop it around. Sometimes it even exists out in the world, but you just haven’t found it. But knowing what it is helps you to navigate towards it. At other times your proposed job description will compel people to think about what is needed. I didn’t know I had these powers but the last three jobs I have had came from a real effort on my part to be clear on the context of the work that I wanted, as in the Carnegie Centre work, or to create opportunities to fill in a missing role in the orchestra of people working towards change, as in the City of Vancouver Four Pillars drug policy work and as in my current role as director of the Canadian Drug Policy Coalition, an organization I co-founded with a number of other Canadians committed to working together to reform Canada’s badly outdated drug policies.

Know that this is a critical time for social change. The structures and systems of the past have been found to be wanting in so many areas— economics, climate change, drug policy, housing to name a few—and there are real generational shifts and accelerations taking place that you will be a part of. Just ask dear Greta Thunberg who spoke so eloquently on Friday (October 25) about the need for climate action. Listen to her speech in Vancouver and learn from it.

Be bold. Think bold, take risks, but be strategic. It is past time for bold action on any number of issues we face every day here in Vancouver and Canada.

Canada’s response to the devastating loss of almost 13,000 people to illicit drug toxicity deaths in the past three years and three months has been pathetic and bound by blinkered thinking; stubborn adherence to policies that have failed miserably; and risk averse bureaucracies and politicians who refuse to even learn enough about the reality of this disaster, its impacts on families, and communities to be able to converse intelligently in public about the potential interventions that might work to stop this epidemic. The inability to even say the words that represent new and bold ideas in this recent election campaign is astounding.

Some have even weaponized ideas that are in fact at the leading edge of public health and social justice thinking. One politician accused the leader of a party of planning to legalize hard drugs if elected—something she implied would be tantamount to chaos in our communities and death for our young people! We already have chaos and death and transnational organized criminal organizations selling drugs to our youth. That is the result of our current approach. She had no idea that the recommendations from two of Canada’s largest health authorities were just that: create a legal regulated market with currently illegal drugs. The Chief Medical Health Officers for Vancouver Coastal Health, Patricia Daly, and Toronto Public Health, Eileen de Villa, have both called for a legal regulated supply of opioids for people who use them so that they stop being poisoned to death in numbers that are at historic levels.

If our politicians have diverged so far from the evidence and advice of senior public health officials in the context of a national public health emergency, we have some major knowledge translation work to do!

Words matter. Find those new ideas and say them loud and often. Write about them. Put them on the record in your conversations with your bosses, your peers, and your community and institutions of government. Put them on the record in public hearings and processes. This will breathe life into them.

Learn how to say things to leaders and others with power that make them uncomfortable. It’s an art to do this, but start getting better at it. If something looks like an absurd way to proceed, it probably is—so say it!

And of course, always challenge yourself. Don’t get too comfortable in your work. Don’t become part of an “industry” servicing these complex societal problems within institutional systems that so often resist real change. This is a time of reconciliation with Indigenous peoples, and a time when maintaining the status quo is killing people, a time when it is imperative to plan for and support engaging people with lived experience in all aspects of research and program development and implementation. Work from within if you are within. Institutional change is an important part of the way forward. There are thousands of willing people and many resources that can be harnessed to support radical change within in many community institutions in my opinion.

And lastly, go find your peeps in other places. Go to international conferences that engage people working on the frontlines of responding to critical health, social, and economic crises globally. I often get asked how I continue to do this work after so many years of pushing for change that never seems to be coming fast enough. My answer is that there is an amazing global community of people in every country working hard to overturn draconian, harmful, and misguided drug policies that are causing immense harm to communities around the world. When we all get together it is powerful and accelerates our learning. We gain perspective, knowledge, and come to know that we are not alone in what is a global movement for change. And of course, the parties are spectacular!

Best to you all at Adler in the coming months and years. May the road rise up to meet the class of 2019. I am so thankful that you are here!

Thank you very much.