Long-established medical practice supports prescribing pre-loaded syringes of epinephrine to people having severe, life-threatening allergic reactions to allergens such as bee stings, nuts and shellfish. Patients, including children, are taught how to use them and carry them with them at all times in order to administer the drug without delay when they have a reaction. It “buys time” to allow the person to get to emergency medical care for monitoring and further treatment if needed. Epinephrine is considered an emergency drug and in most circumstances is administered by trained medical personnel in health care settings. However, the risk of death from a severe allergic reaction, when seconds count, outweighs the risks associated with dispensing the drug for unsupervised use by lay people in the community.

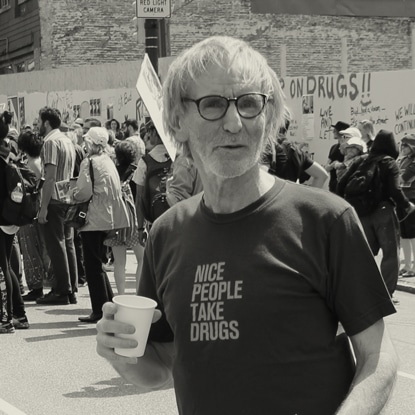

For about thirty years, the harm reduction approach has been advocated by some in Canada as a means of promoting health and preventing needless injury and death among people who use drugs. It accepts that, whatever one’s beliefs about drug use and the people who use drugs, at any given time some people will use drugs unsafely. It holds that preventing unnecessary morbidity and mortality is best accomplished by a continuum of strategies which include educating drug users about the drugs they use, the risks involved, ways to mediate those risks, and the availability of supports to reduce or cease risky use.

For example, research from Australia has shown that needle exchange programs prevented 32,000 HIV infections and almost 100,000 Hepatitis C infections in the first decade of the 21st century, saving over AU$1 billion – which represents a five-fold return on investment. Despite decades of robust evidence supporting the efficacy of harm reduction, in general health care providers have been “slow adopters” of harm reduction strategies.

In September 2010, the College of Physicians and Surgeons of Ontario (CPSO) described widespread addiction to strong painkillers, known as opiates, as a “public health crisis” in Ontario. Earlier this year, a potent long acting opiate known as OxyContin was removed from the Canadian market and replaced with a new formulation called OxyNeo, which is made with a time release coating which is more difficult to bypass, making it less accessible to people using it without a prescription. This has resulted in fewer people using the drug, but not fewer people addicted to opiates.

Research from the United States shows that many former Oxycontin users turned to more readily accessible opiates such as fentanyl and heroin after Oxycontin was taken off the market there.Reports from police and addiction workers suggest the same is now happening here in Canada. One of the problems with this is that people have had to change from opiates with a precisely known strength to others with variable potency. The risk of overdose has increased as a result. Recognizing this, Ontario Health Minister Deb Matthews announced in April 2012 that her government was increasing resources to address opiate addiction, including distribution of “emergency overdose kits across the province.”

Similar to the way in which we provide emergency epinephrine to people with life-threatening allergic reactions, distributing a drug called naloxone, which reverses opiate overdoses, has been saving the lives of people who have overdosed on opiates since 1995 in the UK and Germany. There are 150 such programs in 19 American states but so far only Toronto and Ottawa have naloxone distribution programs up and running in Ontario, eight months after the health minister’s announced support of the strategy.

Naloxone distribution involves providing opiate users with education on overdose prevention, first aid, CPR, as well as naloxone administration in an overdose situation, which “buys time” to get someone to emergency care. The OHRDP received Ministry of Health funding to create a detailed guidance document, which they have compiled building on the work of the Toronto and Ottawa pioneers. It is replete with supporting documentation, current statistics, training manuals, sample protocols and medical directives (required legally to prescribe and dispense this medication to lay people). The naloxone has been purchased and is ready to be used by trained lay people.

Few health care providers would argue that the opiate addiction crisis has gone away. Small communities are dealing with issues like heroin which they have never seen before. What is different in small communities is that the people using substances are much more dispersed and invisible (for more information, see “Below the Radar”). While it may be reasonable in large cities to focus overdose prevention in places where there are high concentrations of drug users, small towns need a more widespread system of interventions because the people affected are not to be found in a few highly visible areas.

For example, Peterborough ranks seventh highest in the province for opioid related deaths. Peterborough Police Chief Murray Rodd has warned that “already we are seeing an increase in heroin and fentanyl in our city,” which he is concerned will lead to “even more overdoses in the coming months”. A network of Peterborough agencies is poised to roll out an evidence-based overdose prevention program, which includes naloxone training – the first for an Ontario county which includes many rural communities where 911 response times are longer than is common in large cities. Supported by the local Medical Officer of Health, the police service and EMS, it will only reach the people it needs to if local health care providers get behind the initiative. One hopes that they will do so without delay, as the project will undoubtedly save lives and provide a model for other small and rural communities.

One of the reasons we study epidemiology (what is causing injury and death) is to use that information to plan programs which will prevent unnecessary injuries and deaths. Health providers have an obligation to understand evidence based interventions available around opioid addiction and to use them to reduce deaths. Some may ask “is this really needed?” but when overdose death rates are so well documented, the answer is obvious. Saving even one person from a needless overdose death should be considered important. She is someone’s daughter, maybe someone’s mom. While the needs of opiate users may not resonate with health care providers in the same way as the needs of people severely allergic to bee stings, when we have an evidence-proven lifesaving intervention, we are obligated to offer it widely and without delay.

-Kathy Hardill

Kathy Hardill is a Primary Care Nurse Practitioner at a clinic which includes patients whose health is made vulnerable through homelessness, poverty and other risk factors. This blog post was originally published on HealthyDebate.ca

At a recent meeting of the

At a recent meeting of the