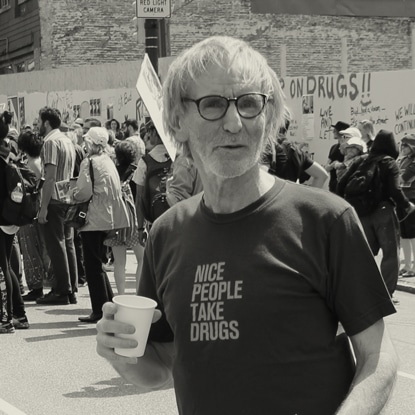

On April 9, the Canadian Drug Policy Coalition along with End Prohibition, PIVOT Legal Society, the Vancouver Area Network of Drug Users (VANDU) and Western Aboriginal Harm Reduction Society will host free public event featuring author and professor, Ernest Drucker.

The event will begin at 7pm at Pivot Legal Society’s offices, 121 Heatley Street in Vancouver.

Author of Plague of Prisons: The Epidemiology of Mass Incarceration in America, Earnest will be speaking about the war on drugs in the USA and the potential consequences of the Canadian Conservative government’s new crime legislation.

To get you warmed up, below is a segment of a book review written by Craig Jones, PhD, Former Executive Director, John Howard Society of Canada previous to the passing of the Omnibus Crime Bill C10.

Every student of epidemiology learns the story of the Broad Street pump (London, Summer 1854), which marks the birth of epidemiology. In A Plague of Prisons, Ernest Drucker uses that story as a metaphor to explain the explosion of incarceration in the United States that followed the 1973 enactment of the Rockefeller drug laws and to illustrate how political decisions act as vectors – pumps – and how these vectors can create a social epidemic of gargantuan proportions, such as the United States coming to incarcerate 1 out of every 4 incarcerated persons in the world.

Drucker’s book can be read in three ways: as an undergraduate introduction to the explanatory power of social epidemiology; as a non-technical analysis of how the United States achieved its historically unprecedented rate of incarceration; and as a warning to Canadians on the propensity of criminalization of non-violent drug users to become a contagion with multi-generational consequences. The book’s timing is apt: Canadians are enacting the political mistakes that produced the plague of prisons in the United States. What were those mistakes?

There were three elements embedded in the Rockefeller drug laws that transformed a public health issue into mass incarceration and transmitted that contagion to the entire country. These include the decision to criminalize drug use; the political reliance on punishment as the appropriate response; and, the attack on judicial discretion through mandatory minimum sentences.

Of the three, the criminalization of drug use featuring large-scale arrests of low-level drug users primed the pump that fueled the contagion of self-sustaining criminality.

There are important differences in the way criminal justice is done between the United States and Canada – some of those differences will insulate Canada from the worst effects of the plague of prisons. But there are a couple of lessons for Canadians too.

The first is that criminal justice policy is too often made in a consequentialist vacuum – that is, without deliberation over downstream effects on families and particularly children of the incarcerated who will likely be the next generation of the incarcerated.

The political imperatives that pushed US policy makers into adopting mandatory minimum sentences appealed to the short-term interests of private prison contractors, correctional officer unions, victims’ advocates, judges and prosecutors. Policies enacted for short-term political opportunity have long-term economic and social consequences, a long tail, but these are of little moment compared to the immediate electoral advantage.

The children of the incarcerated – who are at higher risk of incarceration themselves – have no one to speak for them, at least no one with the clout of correctional officer unions or private prison contractors.

The second lesson is that it is hard to reverse bad policy ideas once they take hold in the public imagination – even once the fiscal costs become unsustainable and the policy itself is clearly failing. As is now clear, the proliferation of mandatory sentencing regimes across the United States has pushed several jurisdictions – Texas, California, Ohio, Florida and New York – to the brink of insolvency, yet they have not achieved rates of crime reduction greater than those jurisdictions that did not embrace draconian sentencing practices.

Worse, the sentencing regimes are hard to unwind because they have created a political constituency where prisons have become a source of high-income, non-polluting jobs.

The third lesson Canadians should heed is that – in seeking to increase the burden of punishment – criminal justice systems engender a self-perpetuating underclass of non-violent but ever more marginalized persons who, because of onerous pardon requirements, may never be reintegrated. They simply cycle through the prison system and transmit the contagion of criminality to their children and family members.

This is a cautionary tale. Canadians would be wise to be more attentive to Drucker’s warnings on the self-sustaining dynamic that emerges out of deliberately growing the rate of incarceration for electoral advantage.